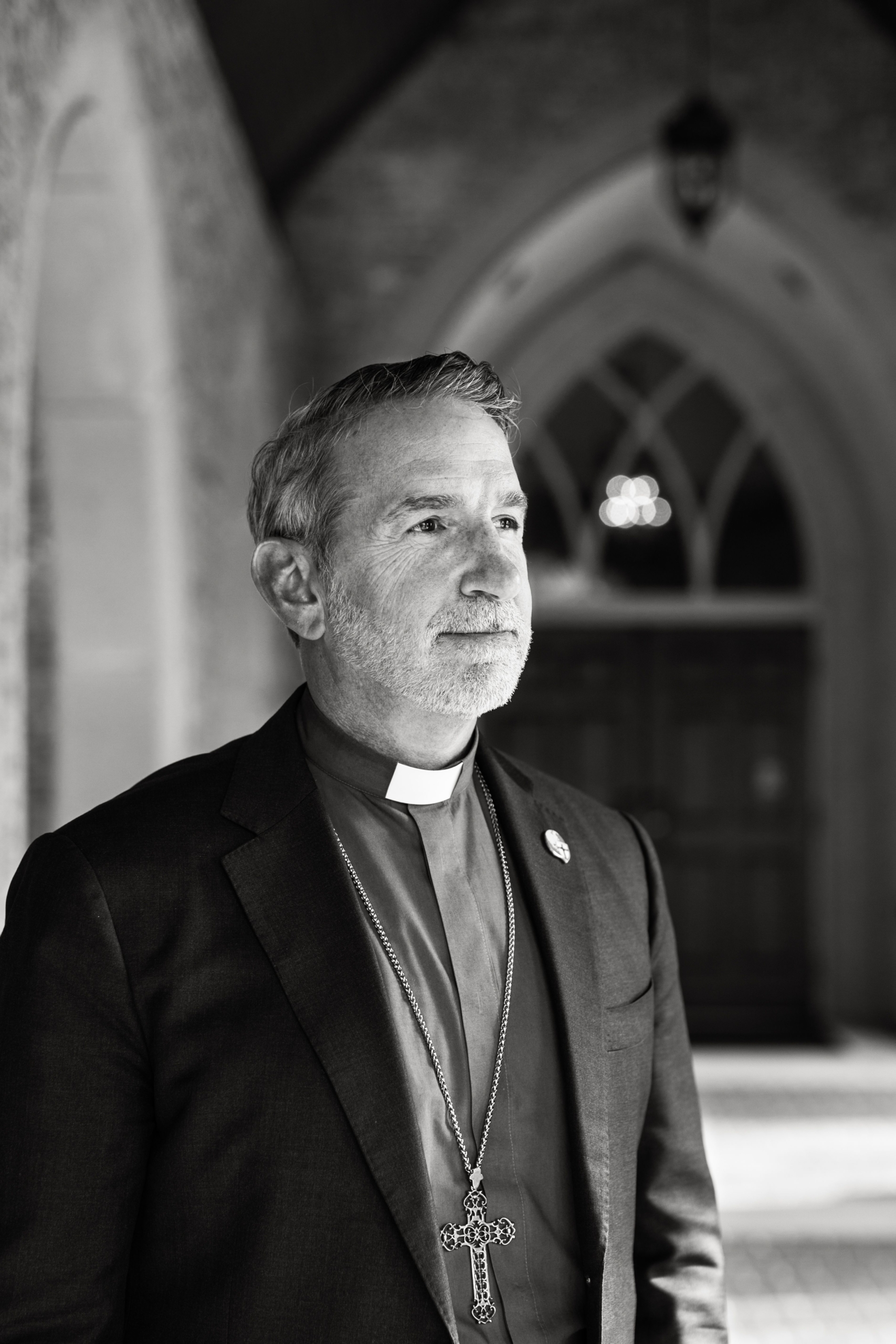

By The Rev. Canon Andrew Gross

“Why is it that someone who is perfectly innocent, Jesus, dying in a brutal way, translates into the forgiveness of sins for someone who is not innocent? Where does that alchemy come from?” This was just one of the questions that had perplexed Anna for years.

Last Fall, she was baptized at Church of the Cross in Boston, Massachusetts, but her com- ing to Christ was the result of years of conversations and hospitality provided by Christians across the globe from Vancouver to Switzerland to Tokyo.

In I Corinthians 3:6-7 the Apostle Paul writes, “I planted, Apollos watered, but God gave the growth. So neither he who plants nor he who waters is anything, but only God who gives the growth.” As God provided steady growth, Anna had many “Pauls” and “Apolloses” in her life.

In Vancouver, the hospitality of the Roman Catholic congregation where her best friend worshiped played a role. Attending after sleepovers at her friend’s house as a child, the sense of the sacred intrigued her. In Switzerland, it was observing the authentic faith of a host family she lived with during a work exchange program. In Tokyo, it was a conversation over dinner which ended in the sanctuary of a commercial-district church plant. In Boston, Christians from Church of the Cross and InterVarsity watered the next stages of her growth.

So how does Jesus save us? How does one understand this alchemy? Her acquaintance in Tokyo explained it like this, “Imagine that your parent loves you so much, and your parent is just, but also full of love for you. Then you do something terrible, you murder someone. Your parent understands that there needs to be justice, but your parent also loves you so much that they want to give you another chance and so they decide to take the punishment for you.”

This explanation of the atonement was the key for Anna: “When I heard that I felt like that was the deepest expression of love that I had ever thought of, could even conceive of, and that, for me, was a tipping point. What I thought was very powerful about that was the parent actually has no control over whether the child will change their ways after sacrificing themselves, so they still leave the agency totally up to their child, but they, out of love, want to give them that chance. The freedom that comes with that love is itself transformative.”

The conversation came during a quick three-day trip to Tokyo, a “reward” for finishing her undergraduate degree in Montreal. When she returned to North America, she began study for her PhD in music theory in Boston.

“When I came to Harvard, the deacon at my church now, Pete Williamson, roped me in to InterVarsity and then through that there was a great process of doing Bible studies and learn- ing more about the story of Jesus, and what it means today, here and now, and feeling like this story relates to me, whereas I never did when I was a child. I joined Church of the Cross. Jeff Banks is a member there and also in InterVarsity. He was my sponsor there and played a huge role in helping me to wrestle with the questions.”

Anna’s full name is Anna Yu Wang. She grew up in Vancouver, British Columbia, and as her name suggests she has a Chinese heritage. “I often just refer to myself as Chinese, without need- ing to add on the addendum that I’m Canadian,” smiles Anna. “Growing up in Vancouver there is a large Asian diaspora, and I never felt different. When I moved to Montreal, and especially Boston, I felt different. I felt like I was normal in Vancouver.”

She also felt different when she visited Asia for her doctoral work in Chinese Opera. Her parents spoke Mandarin in the home, but Anna never really mastered the language. “I’m such a rookie. When I am in China, I feel like I’m dumbed down ten times because I can’t express myself the way that I want to. I can only tell you the baby version of what I really think. That’s really frustrating. If you are a first or second generation diasporic member, and you are now in America or Canada, don’t feel bad that you cannot speak the tongue of your parents perfectly because there are just so many limitations to being able to do so.”

The children and grandchildren of immigrants do not set out to bridge cultural differences, but through their lived experiences they simply find themselves to be a bridge. US sociologist Ruth Hill Useem recognized this phenomenon, and provided a term for it, “third culture kids (TCK).” In an increasingly globalized world, more and more children are learning to find a balance between the heritage of their parents and the norms of their homeland. For many third culture kids, the most comfortable place is with similar peers:

“Living within a community in which there are third culture individuals makes me feel at home because they can understand that tension. When you are with a community of third culture people you can code switch. So often there are ideas in Chinese that I only know in Chinese, and I’ll just sprinkle that into what I’m saying in English, and that enriches what I’m saying despite the brokenness of it from a language standpoint.”

Trained as a classical pianist, Anna is currently learning to play the erhu, a two stringed traditional Chinese fiddle, where the same rules and expectations of western music don’t always overlap: “I’ve begun to realize that nothing is ‘normal.’ Every music has its specificities and contingencies, and they are worth digging into.” Exploring the internal logic of different musical styles and navigating the unique perspectives of differ- ent cultural communities has motivated her to take on a more ambitious endeavor.

Discourse Across Divides

As a summer project, Anna is venturing into dangerous terri- tory: starting online conversation groups on controversial topics in order to try to increase mutual understanding. Despite the polarization of our current cultural moment, Anna is optimistic:

“The norms of discourse can determine the content of that discourse. If we foster a set of norms which are conducive to meaningful exchange then our politics, and our relationships in general, will benefit tremendously from those things. Often when we talk about civil discourse, we talk about it as a tool to reach an end goal, but I think we need to think of this as a social issue in its own right.”

It is easy to be skeptical about such a project, but Anna’s expectations are realistic and her confidence comes from the foundation of her lived experience. She has successfully navigated differences of culture her whole life, and now she’s been baptized into a community of faith that celebrates a God who sent his Son to bridge the ultimate divide. Offering and accepting hospitality and then risking hard conversations is how she has lived. She didn’t set out to bridge a gap, she’s just always been a bridge. It’s simply normal.