Watch the video to learn even more about ETNI.

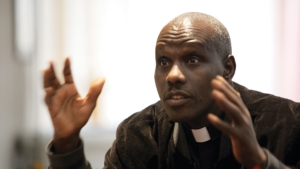

“When I came to the U.S., I had my Masters in Human Resource Management and a letter of recommendation from my Anglican pastor in Kenya because: 1) I needed a job, and 2) I wanted to find a place to worship. When immigrants who are Anglicans come to America, the first thing that’s a challenge is knowing which Anglican church to go to and/or who do you question to find it?” This is a common refrain, and particularly from African immigrants who grew up Anglican. Dennis continued: “You might be lucky to find people who welcome you with open hands as opposed to some who look at you a little suspect. It sometimes feels like they are looking at you asking, ‘Did you come to church to really worship or a handout?’ From the immigrant’s perspective and the church’s, there are adjustments to preconceived perspectives that need to be made.”

In Charlotte, North Carolina alone, Dennis estimates that there are about 2,000 Kenyans: almost half are Roman Catholic, over a quarter are Anglican, and the remaining are non-denominational. The typical East African immigrant who holds a green card* is a professional and is being “hosted.” The host will generally be the connection to a local church. But in addition to the struggles of finding a job and a church community, the families are going through a huge social upheaval. Children are often caught between two cultures: their parents’ culture and the North American culture of their peers. The roles of husbands and wives become challenged as women will sometimes bring home an equal or better salary. “Men are sometimes expected here to cook and do house chores, but culturally in Kenya, I was never expected to do anything in the kitchen. It was completely new to me what I was supposed to do here in America.”

In Charlotte, North Carolina alone, Dennis estimates that there are about 2,000 Kenyans: almost half are Roman Catholic, over a quarter are Anglican, and the remaining are non-denominational. The typical East African immigrant who holds a green card* is a professional and is being “hosted.” The host will generally be the connection to a local church. But in addition to the struggles of finding a job and a church community, the families are going through a huge social upheaval. Children are often caught between two cultures: their parents’ culture and the North American culture of their peers. The roles of husbands and wives become challenged as women will sometimes bring home an equal or better salary. “Men are sometimes expected here to cook and do house chores, but culturally in Kenya, I was never expected to do anything in the kitchen. It was completely new to me what I was supposed to do here in America.”

Amidst the upheaval that can characterize the transition to a new life in North America for many immigrants, ETNI is working to reach the “world at our doorstep.” As ENTI’s Director, the Rev Leah Turner, explained, “Archbishop Foley Beach called us to do more to reach the people that are here from every tribe and nation and so ETNI was formed. A couple of different models have been tried, but in the end it’s about all of us, regardless of what tribe we come from, whether it’s Anglo or whether it is from Kaku, Lua, or Gundam, or any of the tribes across the entire earth. It’s putting aside those designations as barriers and putting our identity as brothers and sisters in Christ with Jesus being the Lord of all of us and celebrating our differences. God made us different. We’re not supposed to be the same. But we are one in Christ.”

Amidst the upheaval that can characterize the transition to a new life in North America for many immigrants, ETNI is working to reach the “world at our doorstep.” As ENTI’s Director, the Rev Leah Turner, explained, “Archbishop Foley Beach called us to do more to reach the people that are here from every tribe and nation and so ETNI was formed. A couple of different models have been tried, but in the end it’s about all of us, regardless of what tribe we come from, whether it’s Anglo or whether it is from Kaku, Lua, or Gundam, or any of the tribes across the entire earth. It’s putting aside those designations as barriers and putting our identity as brothers and sisters in Christ with Jesus being the Lord of all of us and celebrating our differences. God made us different. We’re not supposed to be the same. But we are one in Christ.”

The ETNI gathering began with the centering calm of Morning Prayer, led by Nigerian-American, the Rev. Sulmane Maigadi, and the Rev. Herb Bailey II, a leader in the Matthew 25 Initiative (M25i). From this common understanding of magnifying our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ who has opened the way for all peoples to commune together with the living God, the group turned to listening to each other as they grappled with the turbulence that characterizes the lives of so many trying to make a home in North America.

The ETNI gathering began with the centering calm of Morning Prayer, led by Nigerian-American, the Rev. Sulmane Maigadi, and the Rev. Herb Bailey II, a leader in the Matthew 25 Initiative (M25i). From this common understanding of magnifying our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ who has opened the way for all peoples to commune together with the living God, the group turned to listening to each other as they grappled with the turbulence that characterizes the lives of so many trying to make a home in North America.

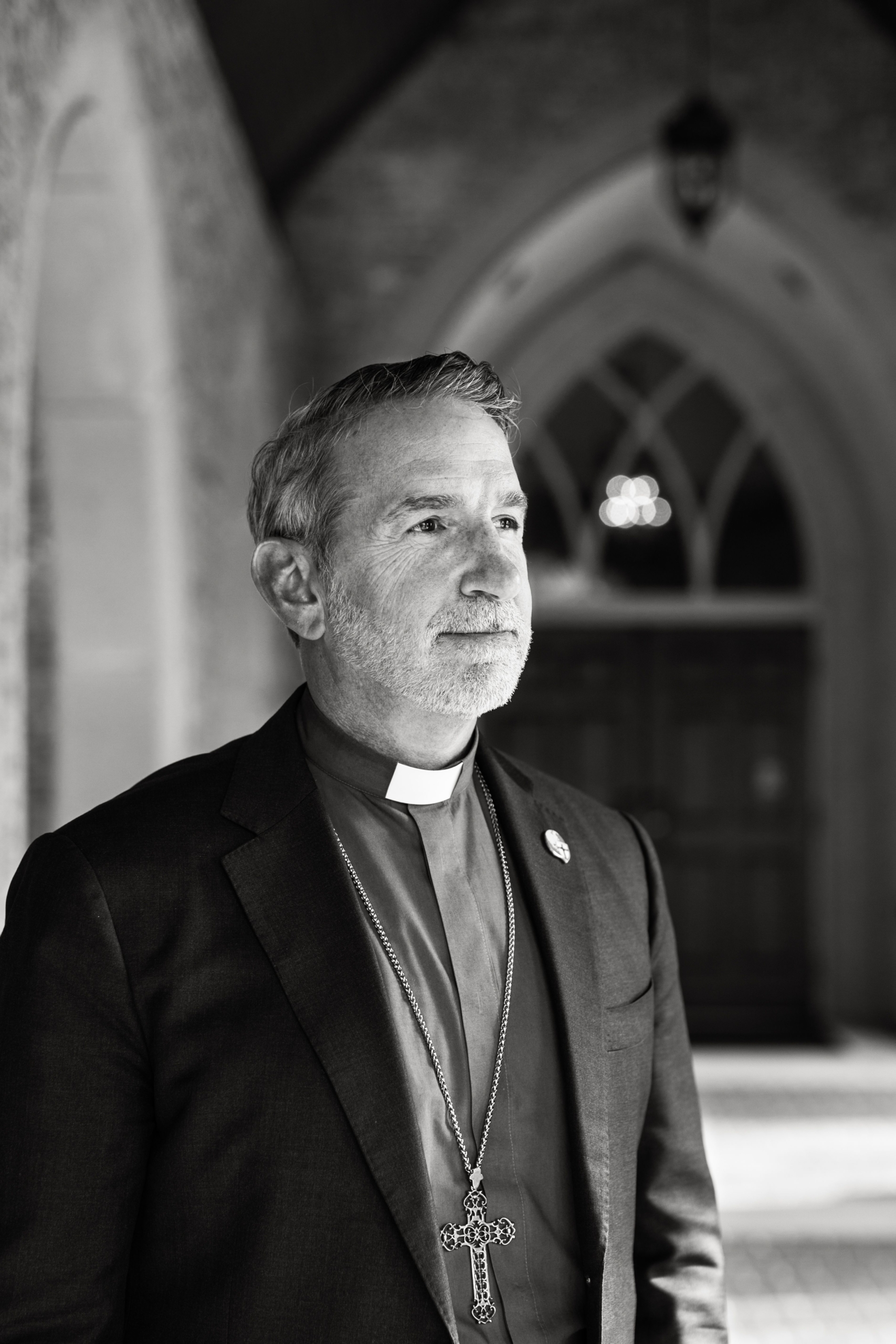

The Rt. Rev. Alan Hawkins, Bishop Co-Adjutor of the Diocese of Christ Our Hope, preached, “I’ve discovered in the Book of Revelation, that the end of all things, the great telos of God is that there will be every tribe, every tongue, every people in every nation. What intrigues me the most about this phraseology is that it is nascent, it is latent, and it is rampant. It’s nascent in the very early pages of the whole Bible. God calls Abram and says, ‘I will make you by following me in faith, trusting in me. I will make you a great nation.’ And then we see that it becomes latent. It’s all over the prophets.

The Rt. Rev. Alan Hawkins, Bishop Co-Adjutor of the Diocese of Christ Our Hope, preached, “I’ve discovered in the Book of Revelation, that the end of all things, the great telos of God is that there will be every tribe, every tongue, every people in every nation. What intrigues me the most about this phraseology is that it is nascent, it is latent, and it is rampant. It’s nascent in the very early pages of the whole Bible. God calls Abram and says, ‘I will make you by following me in faith, trusting in me. I will make you a great nation.’ And then we see that it becomes latent. It’s all over the prophets.

It’s in Jesus’s injunctions to the church. Go into the world and preach the gospel and make disciples of all nations. But then when we get to the Book of Revelation, it’s rampant. Why does it appear? Seven times in all these different combinations and structures, and that is because what God is up to and has been from the beginning is creating for himself one family. One people. One tribe.”

Sergio, Biblical Counselor at Church of the Redeemer and ETNI Coordinator for the Anglican Diocese of Christ Our Hope, explained the complexities in working with what in North America is often classified as one ethnic group, “His- panics” or “Latinos:” “We are 30 different countries with very different cultures and ways of speaking Spanish, Portuguese, or other indigenous languages. Reaching a Mexican is very different from reaching a Chileno. And then third or fourth generation Hispanics who are very established can be quite different from first-generation immigrants who can be low-income with limited education.”

Sergio, Biblical Counselor at Church of the Redeemer and ETNI Coordinator for the Anglican Diocese of Christ Our Hope, explained the complexities in working with what in North America is often classified as one ethnic group, “His- panics” or “Latinos:” “We are 30 different countries with very different cultures and ways of speaking Spanish, Portuguese, or other indigenous languages. Reaching a Mexican is very different from reaching a Chileno. And then third or fourth generation Hispanics who are very established can be quite different from first-generation immigrants who can be low-income with limited education.”

Sergio notes that culturally, families are extremely important. The church can not only play a key role in sharing the gospel, but it can also help support immigrants, both by bringing families together and offering counseling. Practically, he suggests the church focus on relational activities like small groups and dinners.

Sergio notes that culturally, families are extremely important. The church can not only play a key role in sharing the gospel, but it can also help support immigrants, both by bringing families together and offering counseling. Practically, he suggests the church focus on relational activities like small groups and dinners.

As another, long exclamation of “GOOOOOAL” wails from someone’s smartphone in the room, those gathered are reminded that events somehow involving soccer probably would not hurt in reaching the Hispanic demographic.

As a counselor though, Sergio sees that many have gone through great trauma in coming to North America – perhaps a traumatic event motivated them to move. “Counseling is a way to reach them and share the gospel because they bring their own problems,” Sergio said. “They may have a job and more money now, but sometimes they may be worse off because they come with broken lives and families.”