By The Rev. Canon Andrew Gross

As the pandemic began, a prodigy, a 60-something bishop, and a “who’s who” of the Bluegrass scene came together to work on a collaborative album about death, hope, and the power of the resurrection.

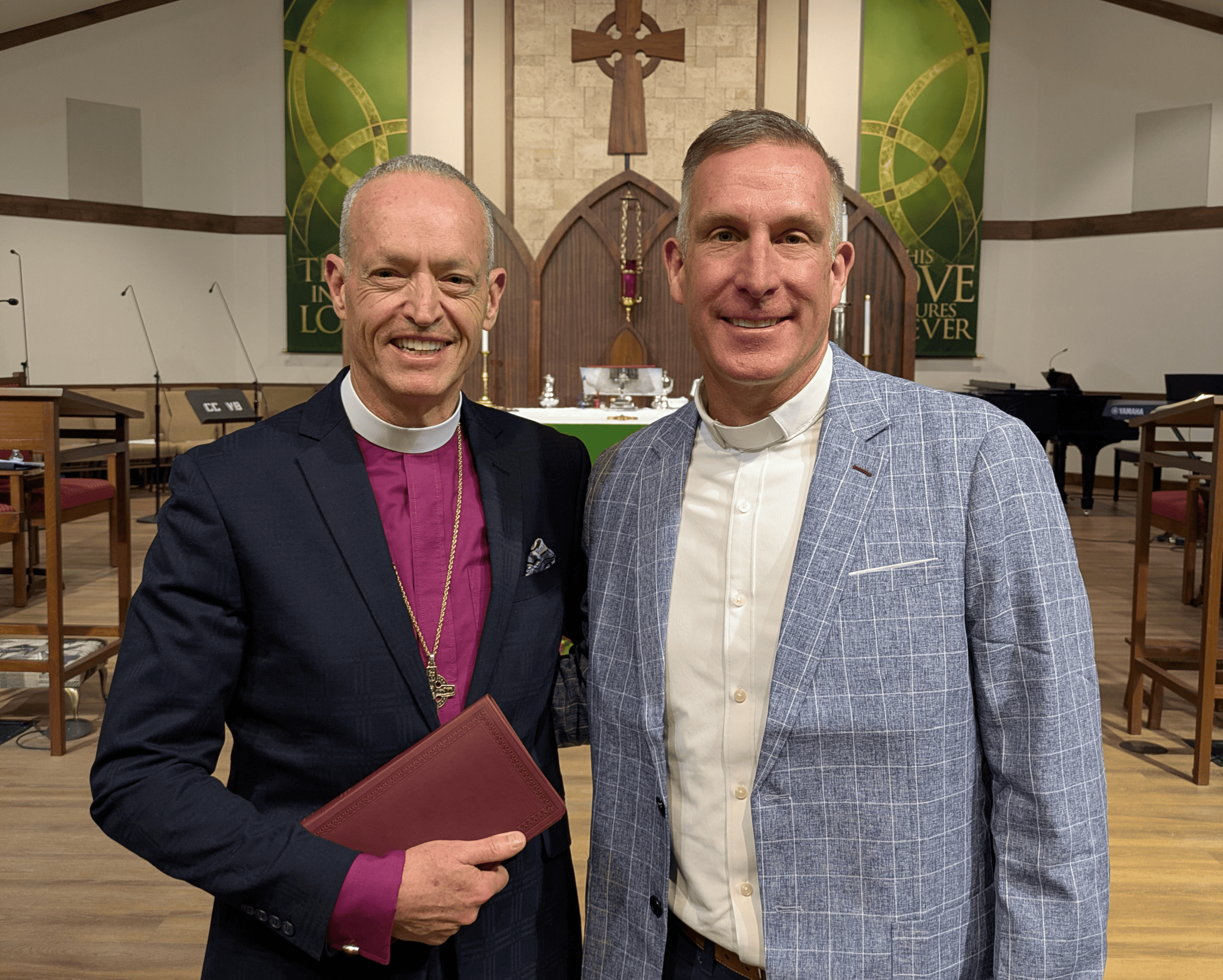

The Rt. Rev. Quigg Lawrence, Rector of Church of the Holy Spirit in Roanoke, Virginia and an Assisting Bishop in the Anglican Diocese of Christ Our Hope, initially started the project as a gift to his mother who was dying of cancer. “Music has always been a part of my family. My father started a band in college, and I eventually served as the manager for the group until I went to college myself. I’ve listened to bluegrass nearly every day of my life since I was 12. I wanted to do something that would honor my mom and share the Gospel,” said Quigg.

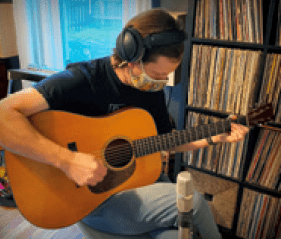

Scott Muldahill, who Quigg had come to know over the years, worked as a producer on the album, lining up suddenly-out- of-work musicians whose tours had been cancelled due to Covid. Quigg found himself in a studio surrounded by Nashville talent, “It was awesome. They were all really supportive. And I appreciated Scott’s honesty. I sang on some of the tracks, but on others he’d level with me; ‘No, that song’s too hard for you.’” Annie Lawrence (Quigg’s daughter, and a musician in her own right) came over to the studio to sing on “Come to Jesus.”

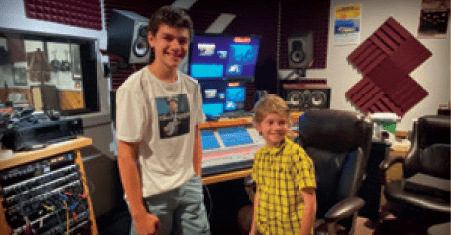

Two of Holy Spirit Roanoke’s junior members, the aptly named Young brothers (aged 14 and 10 when the project began), also played a role in the project. Ayden’s and Blane’s fingers fly across the banjo and mandolin, respectively, throughout “Little Birdie.” Both brothers’ musical training began with classical piano pieces, but Blane has gravitated to the mandolin. Ayden’s musical development changed the day he found a dusty old banjo at his grandparent’s house. The local music shop tuned it up, and after just two years of practice, Ayden took second place in the prestigious Galax bluegrass festival. Ayden admitted to being pretty nervous playing alongside some of his musical heroes on this album: “I’d never even met them before, and then I was playing with them! That was a big day.”

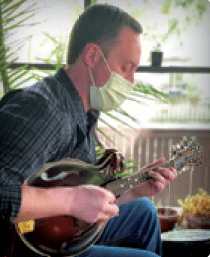

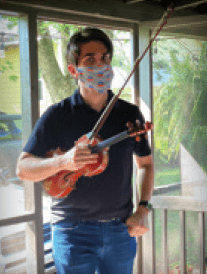

As Covid restrictions shifted, other tracks were produced remotely across state lines. The husband and wife team of Justin Moses and Sierra Hull recorded the dobro, mandolin, guitar, and fiddle in their house and sent the recordings to Scott. He laid down the bass, and with the instrumentation finished, sat with the members of Holy Spirit Roanoke to record their vocals.

It was during that recording the album, “Come Home,” got its name. The words come from the chorus of the album’s last song, “Softly and Tenderly.” The track is the least bluegrass-y of the set, but it fit the theme perfectly and worked. Its inclusion came about by accident. Quigg relays the story: “One of our worship leaders, Julie, was just singing in between takes of the other songs, and Scott said, ‘Oh wow. That’s reeeally good. Keep going!’”

Despite the role some Holy Spirit Roanoke members and the worship team played in its production, Quigg is clear that it isn’t a worship album and it’s not a Holy Spirit Roanoke album. It’s a collaborative bluegrass album. The songs are unique covers of nine songs taken from standards in the bluegrass canon. But that doesn’t mean the Gospel isn’t there both implicitly and explicitly. A bonus tenth track is a short and remarkable eulogy delivered by Country Music Hall of Fame musician, Ricky Skaggs on the occasion of the death of bluegrass legend Dr. Ralph Stanley. Stanley, whose voice became known to a popular audience through the movie “O Brother Where Art Thou,” sang about the Gospel his whole career, but didn’t come to know Jesus until late in life.

Despite the role some Holy Spirit Roanoke members and the worship team played in its production, Quigg is clear that it isn’t a worship album and it’s not a Holy Spirit Roanoke album. It’s a collaborative bluegrass album. The songs are unique covers of nine songs taken from standards in the bluegrass canon. But that doesn’t mean the Gospel isn’t there both implicitly and explicitly. A bonus tenth track is a short and remarkable eulogy delivered by Country Music Hall of Fame musician, Ricky Skaggs on the occasion of the death of bluegrass legend Dr. Ralph Stanley. Stanley, whose voice became known to a popular audience through the movie “O Brother Where Art Thou,” sang about the Gospel his whole career, but didn’t come to know Jesus until late in life.

It’s about being saved.

It’s about being born again…

At Stanley’s funeral, his friend Skaggs shared: “When my dad passed away, so many people was coming up and saying, ‘Oh Ricky, I’m so sorry you lost your dad,’ and when mom passed, ‘I’m so sorry you lost your mom.’ And as nice as I could be, I appreciated the sentiment, but I said, ‘Well, you know when you’ve lost something, you don’t know where it’s at… but I didn’t lose my folks, they are in heaven. I know exactly where they are. I know they’re there. [Ralph] told me, he said, ‘Rick, I’ve sung about God all my life and I didn’t know him.’ Now folks that could be any of us. We could go to church every Sunday and every Wednesday, every time the doors are open, we could sit there and listen to good preaching, and go through the motions of being a Christian, being nice. Nice does not get us to heaven. It ain’t about being nice. It’s about being saved. It’s about being born again… I know where Ralph is, and he ain’t a bit lost. He is totally found.”

Quigg’s mother found her way home before the album was finished, but Quigg is thankful for how it has all unfolded: “The album honored my mother, in the midst of the pandemic it provided a little income for some great musicians, but most importantly, it points people to Jesus.”