Interview by Mary Ailes

Ernie Didot is a professional photographer and videographer, and a member of the Anglican Church of the Incarnation in Harrisonburg, VA. Recently he collaborated on photography exhibit that drew attention to the challenges facing refugees in the Shenandoah Valley.

Tell us about yourself—were you born and raised in Harrisonburg, Virginia? Have you lived there all your life? What makes the community special to you?

I’m a native Virginian, born in Richmond, but was mostly raised in what some around here call, “The State of Northern Virginia.” So I was a Washington, D.C. suburban boy and it was not until I went to college at James Madison University here in Harrisonburg that I discovered life outside of the big city or suburbia. I remember my first stroll through a farmer’s chicken house and later recounting with horror to my suburban friends the culling process. Wide-eyed and bushy-tailed, what felt very “rural” to me at the time began to grow on me. I fell in love with the people, the Valley, and the mountains.

At the time I went to college in the 80’s, the most I saw of people of color in the Valley were the migrant apple pickers (even though there was an African-American community in town, I really wasn’t aware of it). Fast forward 25 years later and the school system is now made up mostly of people of color and/or people who speak English as a second language. Because of the poultry industry and the supply of low-skill jobs, the Shenandoah Valley is an attractive relocation area for refugees. The three universities in the area, the agriculture, the international flavor, the deep Anabaptist roots, plus other industries in the area like Merck and Coors combine to make a unique mix of people. Harrisonburg is called “The Friendly City,” and I think for good reason.

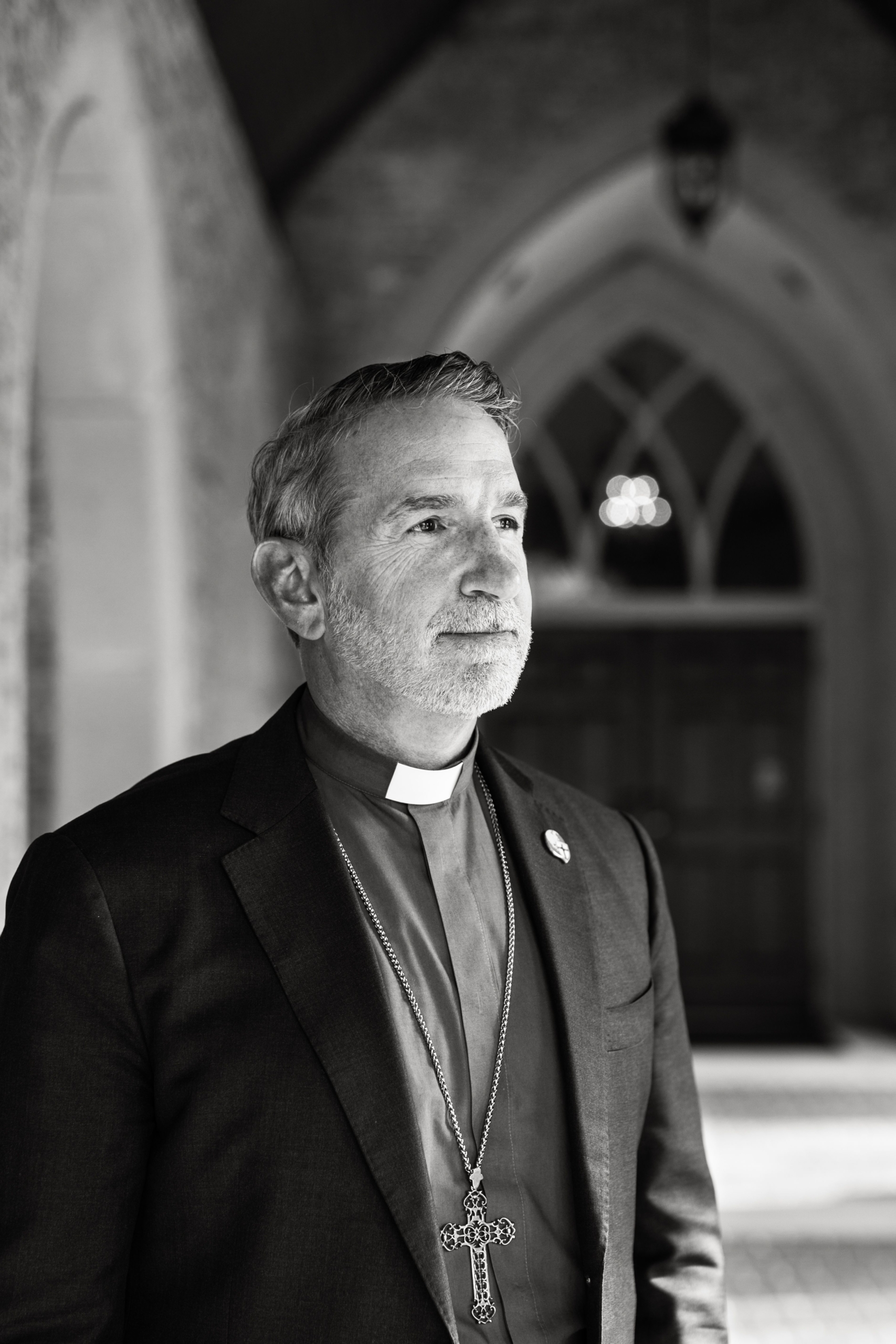

You are an Anglican Christian, a member of Church of the Incarnation in Harrisonburg. How did you come to be a part of that community?

I have grown up in the mainstream evangelical currents of America. When I returned with my wife and children from Guatemala, we wandered for a while looking for a church that magnified Christ, held a high view of Scripture, and demonstrated the fruits of the Spirit in the church community. We found it in an Episcopal church plant here in the Valley, but shortly after joining the church we all went through the turmoil that many experienced in those years with the crisis in the Episcopal Church. We were part of a group of families and friends in the church who decided to plant an Anglican church in the Valley in 2010. We have all been blessed beyond measure with our church family and Rector Aubrey Spears. We have helped plant two churches now in Elkton, Virginia and Crozet, Virginia (very close to Charlottesville) and we are at another point of decision as we have reached maximum capacity again.

You work in video and photography helping clients to tell their story. What made you decide to center your work on video and photography?

My wife and I served in Christian relief and development for eight years in the highlands of Guatemala. Three years into our time there we saw the need to help provide educational material that the people could understand both linguistically and culturally. Since many of the people we worked with were pre-literate, we began producing videos and training them to produce their own videos in their own language and culture. I have since gone on to work with people around the world in helping them tell their story or tell stories that help better communicate their message. We saw how, when the gospel or quality-of-life messages were communicated in story form and in their language and in their culture, they were obviously more inclined to understand, absorb, and make life changes.

One of my favorite things to do is produce video portraits of people and how God uses them in their vocations. Lately I have been working with the Our Daily Bread devotionals in these types of productions, which have taken me to Haiti, Kenya, and Guatemala.

I’ve only recently come back to photography after sharing a studio with a professional photographer named Howard Zehr. Howard is a rock star in the Restorative Justice world and through him I saw how he integrated the use of photography to teach restorative justice. For instance, he returned this summer to a Pennsylvania penitentiary to photograph “lifers” whom he photographed portraits of 25 years ago. Howard participated with me in this Refugee Resettlement project. He is a great man.

Currently, as we are conducting this interview, your photographs are on exhibit in Harrisonburg in a show called “Refuge in the Valley: Portraits of Hope,” that focuses on the settlement of refugees in the Harrisonburg area. What caught your attention about doing this project?

How did you go about “telling the story” of a refugee through your photos? What do you look for to convey their story?

I was one of three photographers. We all decided to not show them in the context of where they live, but rather to capture the essence of who they are. We had noticed that sometimes the surroundings of their environment in photos distracted from people drilling down and really connecting with the person. My approach was to ask them to bring or wear something that strongly reflected their identity. For our neighbor, the Congolese mother, I caught her grinning from ear to ear clutching the Bible that was in her native tongue from the Congo. For her daughter, she was in a brilliantly colored outfit and headdress. I struck on a good vein with her when we started talking about hymns and worship songs from her homeland—I even had her playing and singing the music she enjoyed as the photos were being taken. One of my favorites (but didn’t make the cut in the actual show) was of her lifting her hands in praise to God. I had just asked her what brings her most joy and she said, “Praising God.”

A trio of Cuban men were particularly interesting. Two of them were high ranking in the Havana police force and the third had succeeded in escaping on his 17th try! I asked them to stand as a Cuban man would stand, which to my eyes looked like very proud men. They were sharply dressed and would often flash a “V” sign in the photo. They told me that this was the sign of resistance in Cuba against the regime. While all of them were proud, one of them was particularly melancholy because he had left behind his wife and children. The recent change in the Cuban policy meant it would be very difficult for him to bring his family to the States. I think I appropriately caught his sadness.

A 19-year-old Muslim lad named Homza from the Central African Republic appeared to be a bit down, too. He was alone with his mother in a town south of Harrisonburg not known for many Africans or Muslims. He shared that he was sad because he really didn’t receive much of an education in all of his sojourn to the States and he had just missed entering high school. It wasn’t until we started chatting about soccer that I was able to get him to really come to life.

What did you learn from the refugees while you were working on the project?

One thing I learned as we were taking pictures is that family is family. They had the same dynamics as when my family took pictures at the local Olan Mills studio back in the day. With one family, grandma was grumpy, the boy wasn’t smiling correctly for mom, the mother’s outfit needed adjusting every other photo and by the end of the session they were a bickering mess with each other—just like some experiences I recall. The other thing was that even in the relative “safety” of the U.S., they still had fears for family back home. I was looking forward to a photo session with a Yazidi family from Iraq (Mosul region) who had become fast friends with my sister-in-law. I thought that they would jump at the opportunity since we knew them so well, but I think there were concerns of the images getting back to family or friends in their country and putting them in danger for some reason. In the midst of the stresses of everyday survival in this new land, they are still very much engaged, worried, and stressed over family and friends back home.

Why do you think this is important for the community to engage in?

There are a lot of reasons, but the immediate reason is for the two-way street of acclimation: the community needs to see them as real people with the same hopes and challenges that we all face, and the refugees need to hear and see a broader community that welcomes them and wants to know them. The church needs to engage more so that we understand how we can best help them. Without engagement, it is very difficult to understand where they need or want help. We have discovered that many of the refugees are from a strong background in their faith, but are landing in a culture that is declining in its emphasis on faith. Because of the influence of the Anglican church worldwide, but particularly in Africa, we see a real openness to find a home in our church. The liturgy resonates even though we may sing worship songs more stoically, like hymns, which they call “Songs that are sung with your hands by your side.” It is an amazing opportunity at our doorstep.

Sometimes people in the church think that only specially gifted people who know the languages of the refugees are the only ones capable of helping refugees, when really it is more about simply making yourself available to help in the common things of life: transportation to the store and church; keeping an eye out for good housing; pointing them in the direction of a great thrift store; and introducing them to our simple traditions, like Christmas tree cutting and carving pumpkins. The application Google Translator has quickly become my good friend when working with refugees.

How do you see opening up more conversation on refugees improving conversation in other areas of conflict in local American communities, especially after the recent events in Charlottesville, Virginia?

Charlottesville, Virginia, feels like it is in our backyard, being only one hour away. The nation was certainly rocked, but our community felt it particularly hard, furthering an already polarized divide. The shadow side of the Valley is that expressions of anti-immigrant sentiment, symbolic displays of past racial prejudice, and other activities manifest themselves in many ways. The more we hear the refugees stories, play with their children, help them navigate the grocery aisles, and throw snowballs with them for the first time, the more we can all get on with the work of educating, building, and enjoying each other in bona fide community. As a follower of Jesus, this is par for the course and is about making all things new in His kingdom.

The exhibit is called “Portraits of Hope.” Why is hope so important?

I was thrilled with the name. We certainly wanted to communicate that these people, who have made it here on a shoestring having won the lottery-like immigration selection process, all held the common denominator that they had escaped from a seeming dead-end and now had hope for a new life. They have hope now largely because they have security, education, jobs, housing, and freedom. But what many miss and long for is their family, friends, and community. One of the hardest things for them to adjust to is not just the climate with months of cold, winter weather, but what some of them will sometimes call a cold community. Our culture is more indoors on the computer, TV, or video games, even incubated in our cars and offices. As they enjoy their newfound hope, it is important that we demonstrate that there will be hope for connecting with people, to be part of a community again.

How has your faith impacted your work in photography?

Photography, like gardening or carpentry is for others, is simply an extension of how God has equipped me to serve Him in His kingdom. Frankly, I think I am moderate on the scale of photography skills, but I do like people, I love to draw out stories from people, I understand the power of images, and l am a good connector—so if God can put that together in me and my artistic expression to see his church be a light, to be a connector, to be a hospitable welcomer—then life does not get much better.

What role does your family play in your art and work?

My kids were adopted from Guatemala at birth. They are very Mayan in look and skin color, but very American in culture. I do think that when refugees or international students make the connection as to who our children are, that this plays a role in helping break down some barriers and shyness. They have appeared in many videos as “extras” and have helped in the logistics of providing rides and caring for children more times than they probably wanted to, but they have been tremendously helpful.

My wife Katrina is a natural with people and food (she’s a licensed social worker and restaurant owner). We are in a constant state of trying new foods so, of course, this common denominator with other cultures proves to be a salve in all our interactions with international newcomers. It does not take long to discover her in the kitchen by the side of a newcomer.

How may we pray for you as you continue to tell these important stories through photography and video?

As you learn of the stories and hear of the needs, it is difficult to not want to address them. I need to learn where to begin, continue, and end in addressing the needs. I need wisdom in how to continue best in the role as a connector and communicator through the mediums of video and photography.

Mary Ailes is the Director of Communications for the Diocese of the Mid-Atlantic.